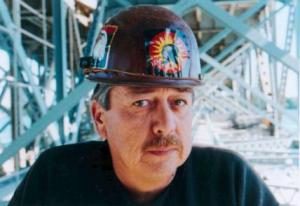

We wanted to take a closer look at funding in the Canadian film industry to try to get a better understanding of how the lurking green goblin played a role in the films we’ve been studying this year. So, we turned to my brother-in-law Joe, who is a Gaffer, or Chief Lighting Technician, in Toronto. Joe’s worked extensively throughout Canada and the United States on films, television, and advertising. I posed these questions to him (on skype, isn’t technology wonderful) the other week, and to the best of my abilities transcribed his words of wisdom. I’ll ask him at Christmas what he thinks.

Without further ado, Interview with an Insider:

In your opinion, is there a visual style that is distinctly Canadian?

My base answer, and one that I think the public would give as well, is that Canadian-made features look like they have a lower budget. However, you have to remember that Canadians aren’t seeing the low-budget American stuff: the films and shows that make it up here are the ones that have the money to make it up here.

The reason that Canadian productions can look so cheap is because, in fact, they are. They may try to look like American productions, but since we straight up don’t have the money, you can tell that they are trying too hard to be outside of their own budget. But, when a Canadian production is shot within it’s means, then you don’t notice it.

One way that the Canadian film industry is starting to distance itself from this reputation, however, is through co-productions, one example of which being the Tudors. In that series lots of money is coming from Canada and it doesn’t look cheap.

As far as style does, I don’t know if there is a distinct visual style though; filmmakers

tend to emulate what has worked well in the past. But then again, in the case of the NFB’s Ryan, people loved his distinct vision and use of animation in a documentary. I don’t know that style used in Ryan would be considered Canadian though, but we’re happy to be proud of it nonetheless.

Also, it’s worth it to point out that when things look good and are Canadian, most people won’t know that and just assume that it’s American. Or again, the Canadian films that look good will be co-productions or have American post-production. Basically, the Canadian film and television industry is low on money, and sometimes that will dictate style more than anything else.

Are there certain techniques innovated by Canadians? How do you think Canada is performed visually, through production techniques? Are there techniques that have become tropes of Canadian films?

In my experience, the source of production is mostly from the States: Vancouver and

Toronto wouldn’t be big production centres if it weren’t for American investment. There’s literally billions of dollars from the States being spent in Canadian cities.

However, almost all the big post-production houses are up here, such as Technicolour and Deluxe. Also, there are a lot of innovations that the average viewer wouldn’t know are Canadian. For example, there are a few models of Canadian camera cars that are used internationally. Camera cars are low-riding trucks with huge trailers where most of the in-car footage would be shot. A couple of the Canadian ones have done movies such as Batman, Transformers 3, and are used in Chicago all the time. Or the lighting company LRX, started in Canada, is now flown in all over the world. Often these sorts of companies will start in Canada, and then be bought up or partnered with bigger companies in the States. There’s a whole service industry in Canada that has made its living off American movies and television shows because of business like this.

As someone who works behind the scenes, do you think your definition of what constitutes a Canadian film differs from others? For you, is the focus on production rather than say something more visible like director, key actors, writers etc? What criteria would you use to define a “Canadian film”?

It’s almost too hard to tell nowadays cause there are so many grey areas. For example, I come up against Canadian ad agencies making commercials for international companies, be they for drug companies, cars, whatever. That sort of work definitely makes it hard to draw a line in the sand between what is Canadian and what isn’t.

In the film world, I’ll see Canadian films shot in the States, but the things are truly, truly Canadian will be local because they’ll have no money to travel outside the country. My experience with explicitly Canadian shows and movies is that they will be very local, very site specific in plot, actors, and production.

As far as Canadian stars go, that process is very similar to the States as well. Most of your funding and your support from investors will come from casting. The filmmaker will go to the investors saying “I’ve got these stars, they will bring in this amount of money” and then whoever is backing the project will do so accordingly. For example, I did just a movie with Margo Kidder and Dave Foley, and even though they weren’t the stars, because the filmmaker will be able to use their name on the DVD cover, they’ll be able to get more funding, more investment. It kinda boils down to a sales tactic.

Though the actors are often the main driving force in getting funding, writers and directors can fill that role too. Canada certainly has darlings: Sarah Polley can’t go wrong these days, so if she wants to make a film, it won’t be as hard for her to get funding as an unknown.

It’s also pretty rare that something Canadian will only be funded by one agency. It’s much more likely that’s you’ll get X-amount from Telefim, X-amount from tax credits, X-amount from a distributor. However, you can only get Telefilm if you have a distributor, and you can only get a distributor if you have an actor’s name. So if one falls through, there’s going to be a domino effect towards failure.

Do you think there are any significant advantages for producing a film in Canada? Or, conversely, outside of Canada?

In Canada you’ll have smaller budgets, and thus fighting all the time over the limited resources. That being said, there’s still going to be fighting on larger budget productions as well. Everyone wants to make their product on the least amount of money possible, which is true for inside and outside of the film industry. It’s why Canada has become such a big production hub: because, back in the day when the Canadian dollar was at sixty cents to the American, the bottom line was that it was just way cheaper to film here.

In the end the film industry is something people make their living off of, and are using to make profit. It’s a very romanticised industry and it does a really good job of self promotion, which gets lots of people out to work for free. You see this in movies made about making movies or behind-the-scenes extras on a DVD. For the most part, it’s a regular job. It’s hard, but also fun. I guess that’s true whether you’re working in Canada or elsewhere.

Canada has relatively small (in budget and size) film production companies. Can you tell us about the pitfalls of dealing with such limits, from the context of your professional background?

The main pitfall is that it’s just so hard to make a living in a totally Canadian industry. Some people can for sure, but to be able to compete with the States and their incredible wealth, you just gotta go down there for a lot of it. Sometimes that can be a little ironic, because filmmakers from Canada will go down to the States in order to contend, but then end up making all their films in Canada cause it’s cheaper to do so here.

So I guess I don’t know how you could encourage more investment and growth in the Canadian film industry. The Québec film industry is really strong within the province, but then again they’ve good the boon of language and a strong culture. I’m not sure how you could foster that in English Canada. I guess you could encourage people to make stuff that people want to see, but you’ll always be competing with the behemoth of the American studio system. Where do you go from there, right?

There have been Canadian successes, just look at Atom Egoyan. But Canadian filmmakers are just competing against such a massive industry. We end up seeing what’s been filtered down to us, but we don’t have the resources to create the amount of content needed for the cream to rise to the top.

Another pitfall is that Canadian filmmakers have to work so hard to make their movies on limited budgets that they just don’t get the practice of making lots and lots of movies. The trope that Canadian writers are writing half of the American comedies we see is probably true. These people would like to make a living out of what they do, and they have to move to America in order to do so a lot of the time. Sometimes they don’t though, and it’s really great to see projects like the Trailer Park Boys taking off. When you can make a Canadian film within it’s means and it does a good job, that’s the most satisfying.

Have you worked with Telefilm of the NFB and, if so, what was your experience like? Working under these companies, was there any encouragement to keep the film as local as possible or were you pushed towards finding the means of completion, whatever the national alignment?

I think these agencies, amongst others, have an odd job because they have limited resources to dole out to a thousand people a day. But they also have to justify it, as opposed to a studio system which can be more cutthroat. With the studio system, you have to make money for the company compared to these agencies who instead have a mandate rather than a bottom line. They do have a political bottom line however. For example, a movie like Passchendaele will get money because it touches on the political points of being about Canada, wartime, and history.

A good way to look at this system is through Québec. Québec supports their own filmmakers, and supports them well. Because these funding agencies have such a good argument in Québec – they know that their films will be seen – then more investment can flow in. I don’t know how you could institute this in Ontario though, because they’ll be more overshadowed by the monolith of the United States.

Then again, American budgets are starting to get smaller as well. It used to be that the standard budget for a comedy film would be $200 million, but now the average budget will be something around $40 million. It’ll be interesting to see if and how this affects the sorts of films being made on either side of the border.